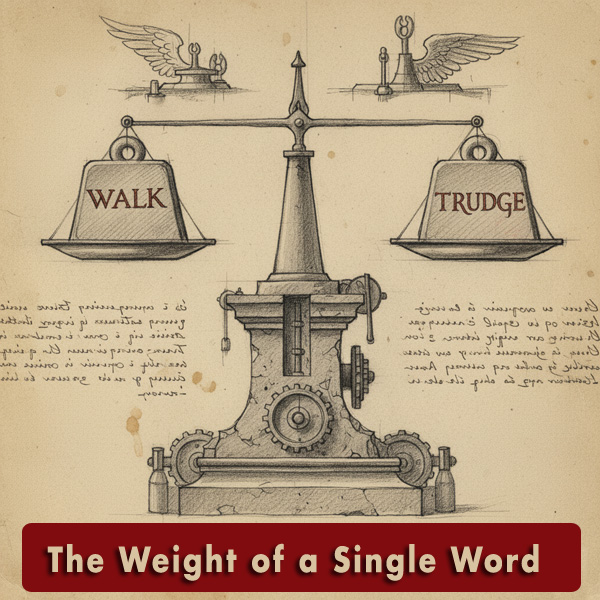

The thesaurus is your friend. But like any good friend, it should tell you the truth, not just what you want to hear.

Consider these two sentences:

The detective walked into the room.

The detective slunk into the room.

Same structure. Same character. Same setting. But one word—slunk instead of walked—transforms everything. Suddenly we know this detective is ashamed, furtive, or trying not to be noticed. We know something about the power dynamics in that room before another word is written.

That’s the magic of precision. One word can do the work of ten.

The Screenwriter’s Edge

Screenwriters live and die by economy. You have 90-120 pages to tell your entire story, which means every word must earn its place. The masters understand this instinctively.

Take Aaron Sorkin. His characters don’t just talk—they spar, they perform, they duel with language. Watch how he builds rhythm through precise verb choices in action lines: characters storm through hallways, explode into rooms, fire questions at each other. Every verb propels the story forward at breakneck speed.

Shane Black takes a different approach. His screenplays read like novels because he understands that word choice creates voice. A character doesn’t just light a cigarette—it’s a cancer stick. A car doesn’t just drive by—it prowls past. Black’s word choices create a specific tone, a noir-tinged world where even mundane objects carry weight and danger.

Taylor Sheridan strips everything down to brutal efficiency. In Sicario, he doesn’t write “The agents prepared their weapons.” He writes “They loaded.” Two words. Maximum impact. Every action line hits like a punch because there’s not a wasted syllable.

Try This: Exercise #1 – The Verb AuditPull up a page from your current screenplay or manuscript. Circle every verb. Now ask yourself: Is this the most precise verb I could use? Does it reveal character, create mood, or advance the story—or is it just occupying space? Replace at least five verbs with stronger, more specific choices. But here’s the catch: your new verbs can’t be longer than two syllables. This forces you to find power in simplicity, not complexity. Examples:

|

The Prose Writer’s Toolkit

Novelists have more room to breathe, but that doesn’t mean imprecision gets a free pass. If anything, prose demands even greater care because readers will spend hours inside your word choices, not minutes.

Consider this passage:

The heat was oppressive. Sarah felt uncomfortable as she moved through the crowd.

Now watch what happens when we apply precision:

The heat pressed down like a wet blanket. Sarah shouldered through the throng, her dress clinging to her spine.

“Oppressive” told us the heat was bad. “Pressed down like a wet blanket” made us feel it. “Uncomfortable” was vague. “Her dress clinging to her spine” was specific, visceral. “Moved through” was generic. “Shouldered through the throng” showed effort, discomfort, aggression even.

The difference isn’t complexity—it’s precision.

The Elmore Leonard Principle: Simple is Not the Same as Simplistic

Elmore Leonard famously advised writers to avoid words that draw attention to themselves. He wrote in plain American English, but every word was ruthlessly chosen. His characters didn’t pontificate—they talked. They didn’t ambulate—they walked. But when Leonard wrote that someone “walked,” you knew exactly how they walked because of the context he’d built around that simple verb.

This is the trap many writers fall into: they think precision means reaching for the five-syllable word, the obscure term, the vocabulary builder. They want to prove they’re smart, well-read, sophisticated.

But precision isn’t about showing off. It’s about showing up with exactly the right tool for the job.

Ask yourself: Am I choosing this word because it’s the perfect fit, or because I want to sound impressive? If it’s the latter, you’re writing for yourself, not your reader. And your reader will feel it—not as admiration, but as distance.

Try This: Exercise #2 – The Simplicity ChallengeTake a descriptive paragraph from your work—maybe a setting description or a character introduction. Now rewrite it using only single-syllable words (with a maximum of three two-syllable words if absolutely necessary). This isn’t about making your final draft monosyllabic. It’s about discovering whether you’re using complex words to convey complex ideas, or just to sound writerly. Often, you’ll find that the simple version is stronger, clearer, and more emotionally resonant. Example: Complex: “The protagonist experienced considerable trepidation as she contemplated the precipitous descent.” Simple: “She looked down the cliff and felt afraid.” Precise: “She looked down the cliff and her stomach dropped.” The third version uses simple words but creates a physical sensation. That’s the goal: precision through clarity, not through complexity. |

Finding Your Balance

The best writers develop an ear for when to reach for the thesaurus and when to trust the simple, direct word. They understand that “said” is often better than “articulated,” that “ran” can be more powerful than “sprinted” if the context supports it, that sometimes “looked” does exactly what you need.

Your job isn’t to impress readers with your vocabulary. It’s to disappear into the story so completely that readers forget they’re reading at all. They’re just there, in that room with your detective, feeling the heat with Sarah, watching your characters move through a world that feels real because every word—simple or complex—was chosen with intention.

The thesaurus is your friend. But the best friend you’ll ever have is the delete key, ready to strike through every word that’s showing off instead of showing up.

For your November workshop on Props and Setting, we’ll explore how this same principle applies to the objects and environments in your stories. Every detail should carry weight. Every description should earn its place. Learn more about the workshop here.